|

Tao Te Ching

THE TAOISM OF LAO TZU

|

Chuang Tzu 18 The Taoist Text, Chapter 18

Perfect Enjoyment.1. Under the sky is perfect enjoyment to be found or not? Are there any who can preserve themselves alive or not? If there be, what do they do? What do they maintain? What do they avoid? What do they attend to? Where do they resort to? Where do they keep from? What do they delight in? What do they dislike?

What the world honours is riches, dignities, lonevity, and being deemed able. What it delights in is rest for the body, rich flavours, fine garments, beautiful colours, and pleasant music. What it looks down on are poverty and mean condition, short life and being deemed feeble. What men consider bitter experiences are that their bodies do not get rest and ease, that their mouths do not get food of rich flavour, that their persons are not finely clothed, that their eyes do not see beautiful colours, and that their ears do not listen to pleasant music. If they do not got these things, they are very sorrowful, and go on to be troubled with fears. Their thoughts are all about the body;- are they not silly? Now the rich embitter their lives by their incessant labours; they accumulate more wealth than they can use:- while they act thus for the body, they make it external to themselves. Those who seek for honours carry their pursuit of them from the day into the night, full of anxiety about their methods whether they are skilful or not:- while they act thus for the body they treat it as if it were indifferent to them. The birth of man is at the same time the birth of his sorrow; and if he live long he becomes more and more stupid, and the longer is his anxiety that he may not die; how great is his bitterness!- while he thus acts for his body, it is for a distant result. Meritorious officers are regarded by the world as good; but (their goodness) is not sufficient to keep their persons alive. I do not know whether the goodness ascribed to them be really good or really not good. If indeed it be considered good, it is not sufficient to preserve their persons alive; if it be deemed not good, it is sufficient to preserve other men alive. Hence it is said, "When faithful remonstrances are not listened to, (the remonstrant) should sit still, let (his ruler) take his course, and not strive with him." Therefore when Tsze-hsü strove with (his ruler), he brought on himself the mutilation of his body. If he had not so striven, he would not have acquired his fame:- was such (goodness) really good or was it not? As to what the common people now do, and what they find their enjoyment in, I do not know whether the enjoyment be really enjoyment or really not. I see them in their pursuit of it following after all their aims as if with the determination of death, and as if they could not stop in their course; but what they call enjoyment would not be so to me, while yet I do not say that there is no enjoyment in it. Is there indeed such enjoyment, or is there not? I consider doing nothing (to obtain it) to be the great enjoyment, while ordinarily people consider it to be a great evil. Hence it is said, "Perfect enjoyment is to be without enjoyment; the highest praise is to be without praise." The right and the wrong (on this point of enjoyment) cannot indeed be determined according to (the view of) the world; nevertheless, this doing nothing (to obtain it) may determine the right and the wrong. Since perfect enjoyment is (held to be) the keeping the body alive, it is only by this doing nothing that that end is likely to be secured. Allow me to try and explain this (more fully):- Heaven does nothing, and thence comes its serenity; Earth does nothing, and thence comes its rest. By the union of these two inactivities, all things are produced. How vast and imperceptible is the process!- they seem to come from nowhere! How imperceptible and vast!- there is no visible image of it! All things in all their variety grow from this Inaction. Hence it is said, "Heaven and Earth do nothing, and yet there is nothing that they do not do." But what man is there that can attain to this inaction?

Having given expression to these questions, he took up the skull, and made a pillow of it when he went to sleep. At midnight the skull appeared to him in a dream, and said, "What you said to me was after the fashion of an orator. All your words were about the entanglements of men in their lifetime. There are none of those things after death. Would you like to hear me, Sir, tell you about death?" "I should," said Kwang-tsze, and the skull resumed: "In death there are not (the distinctions of) ruler above and minister below. There are none of the phenomena of the four seasons. Tranquil and at ease, our years are those of heaven and earth. No king in his court has greater enjoyment than we have." Kwang-tsze did not believe it, and said, "If I could get the Ruler of our Destiny to restore your body to life with its bones and flesh and skin, and to give you back your father and mother, your wife and children, and all your village acquaintances, would you wish me to do so?" The skull stared fixedly at him, knitted its brows, and said, "How should I cast away the enjoyment of my royal court, and undertake again the toils of life among mankind?"

"The marquis was trying to nourish the bird with what he used for himself, and not with the nourishment proper for a bird. They who would nourish birds as they ought to be nourished should let them perch in the deep forests, or roam over sandy plains; float on the rivers and lakes; feed on the eels and small fish; wing their flight in regular order and then stop; and be free and at ease in their resting-places. It was a distress to that bird to hear men speak; what did it care for all the noise and hubbub made about it? If the music of the Kiû-shâo or the Hsien-khih were performed in the wild of the Thung-thing lake, birds would fly away, and beasts would run off when they heard it, and fishes would dive down to the bottom of the water; while men, when they hear it, would come all round together, and look on. Fishes live and men die in the water. They are different in constitution, and therefore differ in their likes and dislikes. Hence it was that the ancient sages did not require (from all) the same ability, nor demand the same performances. They gave names according to the reality of what was done, and gave their approbation where it was specially suitable. This was what was called the method of universal adaptation and of sure success."

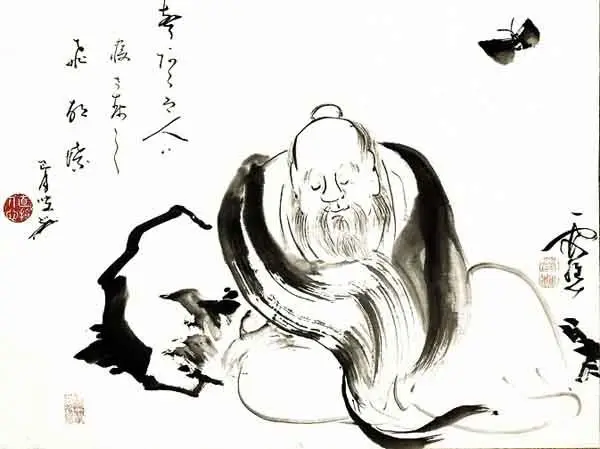

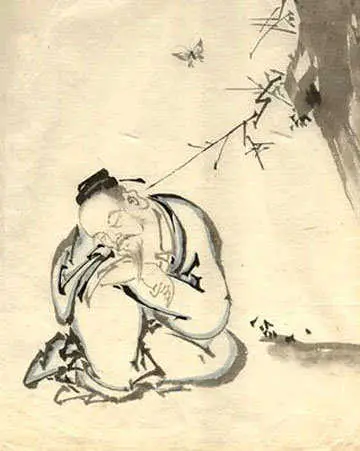

Chuang Tzu

The Book of Chuang TzuA modern translation of Chuang Tzu, by Martin Palmer and Elizabeth Breuilly.See the book at Amazon

About CookiesMy Other Websites:I Ching OnlineThe 64 hexagrams of the Chinese classic I Ching and what they mean in divination. Try it online for free.

Qi Energy ExercisesThe ancient Chinese life energy qi (chi) explained, with simple instructions on how to exercise it.

Life EnergyThe many ancient and modern life force beliefs all over the world explained and compared.

Taoismen på svenska

Other Books by Stefan StenuddClick the image to see the book at Amazon (paid link).

The Greek philosophers and what they thought about cosmology, myth, and the gods. |

Tao Te Ching

Tao Te Ching Tao Quotes

Tao Quotes Fake Lao Tzu Quotes

Fake Lao Tzu Quotes Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients Qi — Increase Your Life Energy

Qi — Increase Your Life Energy Aikido Principles

Aikido Principles Life Energy Encyclopedia

Life Energy Encyclopedia Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Stefan Stenudd

Stefan Stenudd