|

Tao Te Ching

THE TAOISM OF LAO TZU

|

Chuang Tzu 7 The Taoist Text, Chapter 7

The Normal Course for Rulers and Kings.1. Nieh Khüeh put four questions to Wang Î, not one of which did he know (how to answer). On this Nieh Khüeh leaped up, and in great delight walked away and informed Phû-ì-tsze of it, who said to him, "Do you (only) now know it?" He of the line of Yü was not equal to him of the line of Thâi. He of Yü still kept in himself (the idea of) benevolence by which to constrain (the submission of) men; and he did win men, but he had not begun to proceed by what did not belong to him as a man. He of the line of Thâi would sleep tranquilly, and awake in contented simplicity. He would consider himself now (merely) as a horse, and now (merely) as an ox. His knowledge was real and untroubled by doubts; and his virtue was very true:- he had not begun to proceed by what belonged to him as a man.

2. Kien Wû went to see the mad (recluse), Khieh-yü, who said to him, "What did Zah-kung Shih tell you?" The reply was, "He told me that when rulers gave forth their regulations according to their own views and enacted righteous measures, no one would venture not to obey them, and all would be transformed." Khieh-yü said, "That is but the hypocrisy of virtue. For the right ordering of the world it would be like trying to wade through the sea and dig through the Ho, or employing a musquito to carry a mountain on its back. And when a sage is governing, does he govern men's outward actions? He is (himself) correct, and so (his government) goes on;- this is the simple and certain way by which he secures the success of his affairs. Think of the bird which flies high, to avoid being hurt by the dart on the string of the archer, and the little mouse which makes its hole deep under Shan-khiû to avoid the danger of being smoked or dug out;- are (rulers) less knowing than these two little creatures?"

Yang Tsze-kü looked discomposed and said, "I venture to ask you what the government of the intelligent kings is." Lâo Tan replied, "In the governing of the intelligent kings, their services overspread all under the sky, but they did not seem to consider it as proceeding from themselves; their transforming influence reached to all things, but the people did not refer it to them with hope. No one could tell the name of their agency, but they made men and things be joyful in themselves. Where they took their stand could not be fathomed, and they found their enjoyment in (the realm of) nonentity."

On the morrow, accordingly, Lieh-tsze came with the man and saw Hû-tsze. When they went out, the wizard said, "Alas! your master is a dead man. He will not live;- not for ten days more! I saw something strange about him;- I saw the ashes (of his life) all slaked with water!" When Lieh-tsze reentered, he wept till the front of his jacket was wet with his tears, and told Hû-tsze what the man had said. Hû-tsze said, "I showed myself to him with the forms of (vegetation beneath) the earth. There were the sprouts indeed, but without (any appearance of) growth or regularity:- he seemed to see me with the springs of my (vital) power closed up. Try and come to me with him again." Next day, accordingly, Lieh-tsze brought the man again and saw Hû-tsze. When they went out, the man said, "It is a fortunate thing for your master that he met with me. He will get better; he has all the signs of living! I saw the balance (of the springs of life) that had been stopped (inclining in his favour)." Lieh-tsze went in, and reported these words to his master, who said, "I showed myself to him after the pattern of the earth (beneath the) sky. Neither semblance nor reality entered (into my exhibition), but the springs (of life) were issuing from beneath my feet;- he seemed to see me with the springs of vigorous action in full play. Try and come with him again." Next day Lieh-tsze came with the man again, and again saw Hû-tsze with him. When they went out, the wizard said, "Your master is never the same. I cannot understand his physiognomy. Let him try to steady himself, and I will again view him." Lieh-tsze went in and reported this to Hû-tsze, who said, "This time I showed myself to him after the pattern of the grand harmony (of the two elemental forces), with the superiority inclining to neither. He seemed to see me with the springs of (vital) power in equal balance. Where the water wheels about from (the movements of) a dugong, there is an abyss; where it does so from the arresting (of its course), there is an abyss; where it does so, and the water keeps flowing on, there is an abyss. There are nine abysses with their several names, and I have only exhibited three of them. Try and come with him again." Next day they came, and they again saw Hû-tsze. But before he had settled himself in his position, the wizard lost himself and ran away. "Pursue him," said Hû-tsze, and Lieh-tsze did so, but could not come up with him. He returned, and told Hû-tsze, saying, "There is an end of him; he is lost; I could not find him." Hû-tsze rejoined, "I was showing him myself after the pattern of what was before I began to come from my author. I confronted him with pure vacancy, and an easy indifference. He did not know what I meant to represent. Now he thought it was the idea of exhausted strength, and now that of an onward flow, and therefore he ran away." After this, Lieh-tsze considered that he had not yet begun to learn (his master's doctrine). He returned to his house, and for three years did not go out. He did the cooking for his wife. He fed the pigs as if he were feeding men. He took no part or interest in occurring affairs. He put away the carving and sculpture about him, and returned to pure simplicity. Like a clod of earth he stood there in his bodily presence. Amid all distractions he was (silent) and shut up in himself. And in this way he continued to the end of his life.

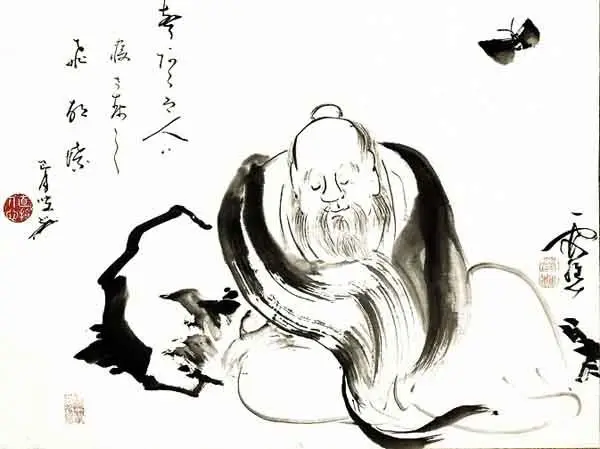

Chuang Tzu

The Book of Chuang TzuA modern translation of Chuang Tzu, by Martin Palmer and Elizabeth Breuilly.See the book at Amazon

About CookiesMy Other Websites:I Ching OnlineThe 64 hexagrams of the Chinese classic I Ching and what they mean in divination. Try it online for free.

Qi Energy ExercisesThe ancient Chinese life energy qi (chi) explained, with simple instructions on how to exercise it.

Life EnergyThe many ancient and modern life force beliefs all over the world explained and compared.

Taoismen på svenska

Other Books by Stefan StenuddClick the image to see the book at Amazon (paid link).

The Greek philosophers and what they thought about cosmology, myth, and the gods. |

Tao Te Ching

Tao Te Ching Tao Quotes

Tao Quotes Fake Lao Tzu Quotes

Fake Lao Tzu Quotes Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients Qi — Increase Your Life Energy

Qi — Increase Your Life Energy Aikido Principles

Aikido Principles Life Energy Encyclopedia

Life Energy Encyclopedia Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Stefan Stenudd

Stefan Stenudd